History

The Royal Caledonian Horticultural Society was established in 1809 by a group of seventeen Edinburgh worthies who met at the Royal College of Physicians. The outcome was the establishment of a Society for the ‘encouragement and improvement of the best fruit, the most choice flowers and most useful culinary vegetables’. Since the beginning, the Society has welcomed skilled professionals, amateurs, nurserymen and professional gardeners. In the early days, as it is now, the activities of the Society were focused on a mix of the theoretical and the practical sides of gardening and horticulture; medals and certificates were awarded and shows were held.

Birth of the Society

At the time the Society was founded in 1809, Edinburgh was in the throes of building of the New Town, though only two of the gardens, St Andrew Square and Charlotte Square, were then laid out. Gardening must have been a subject of fairly wide interest because in December of that year a group of Edinburgh worthies met at the Royal College of Physicians, then in George Street, and from this meeting a Society for the ‘encouragement and improvement of the best fruit, the most choice flowers and most useful culinary vegetables’ was set up. This was the Caledonian Horticultural Society, later to become Royal, and still very much a feature of the Scottish landscape. The inspiration for the Society came from the Horticultural Society, founded in London five years earlier and there were many links between the two societies. Sir Joseph Banks and Richard Salisbury, founders of the London Society, and Thomas Andrew Knight who was President of the London Society from 1811 until 1838, were honorary members from the outset.

Andrew Duncan and Patrick Neill

At the first meeting, and many subsequent ones, the Chair was taken by Dr Andrew Duncan, a professor of medicine at Edinburgh University, and President of the Royal College of Physicians. He was created a life Vice-President and this genial bon-viveur became known as the father of the Society. The Society clearly had social pretensions for the Earl of Dalkeith was elected President. Also at the first meeting Patrick Neill became joint secretary, and he remained in the post for 41 years, until shortly before he died in 1851. He and Duncan enjoyed a very long and productive partnership. Patrick Neill was one of those indefatigable characters of the early nineteenth century with a wide variety of interests. He ran his family printing firm which printed Encyclopaedia Britannica, to which he contributed the entry on gardening. He was a naturalist and antiquarian and was well known for his expertise as a gardener and botanist. His garden at Canonmills in Edinburgh, was famous for the immensely wide variety of plants grown there, including many exotics, and for its menagerie. He played a leading role in the creation of East Princes Street Gardens.

Early Days

From the beginning the Society flourished, bringing together ‘skilful professional gardeners and zealous amateurs’, and the support of nurserymen and professional gardeners was very important. The initial subscription was one guinea a year for ordinary members, but noblemen or gentlemen were invited to join free as honorary members. By 1829 a membership of 1,000 or so had been built up in different categories. Many of the well-known figures of the City joined, among them the artist Henry Raeburn, judge Henry Cockburn and architect William Playfair, and there were strong links between the Society and the creation of the gardens of the Edinburgh New Town. The activities of the Society in its early days had much in common with the present day. Both the theoretical and the practical sides of gardening were covered; meetings were held, papers were read, medals and certificates were awarded and shows were an important feature. The meetings were held in the Royal College of Physicians and one of the first prizes offered by the Society was a silver medal for the best radishes grown in the open ground, awarded to James Thomson, gardener from Duddingston on the edge of Edinburgh, who sent 500 radishes to market on 12th April 1810.

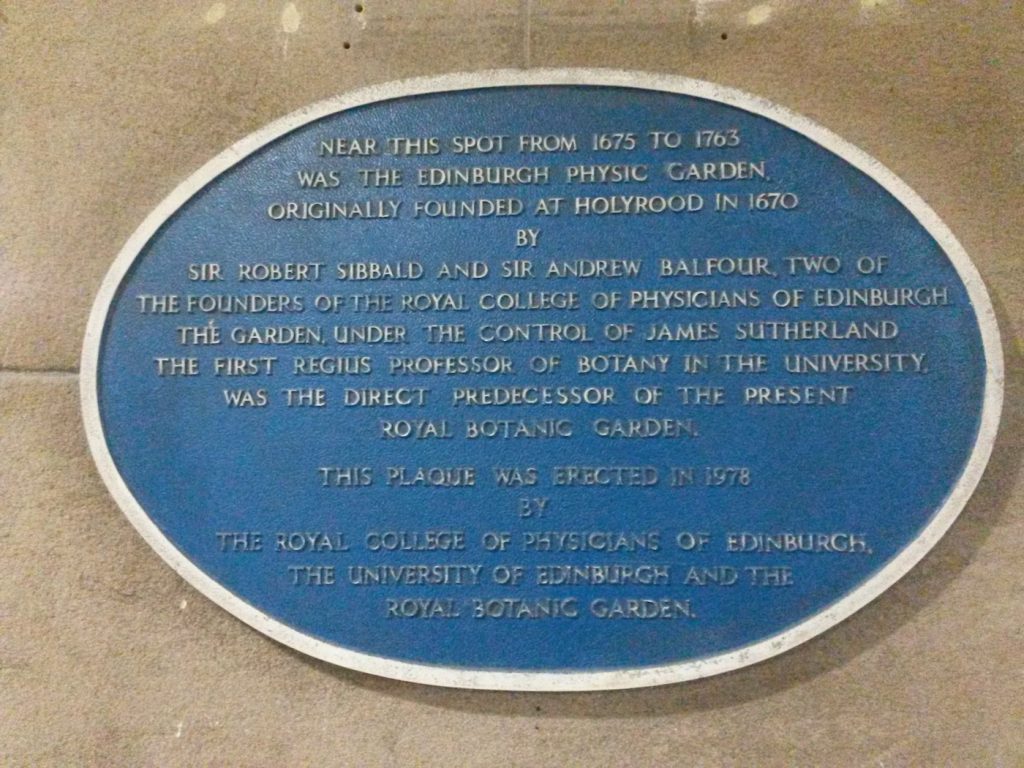

The Experimental Garden

The Society though was ambitious and the creation of a garden, first mooted in 1810, was a high priority. It was partly to fulfil the role of giving advice on the best varieties and methods of cultivation, and partly to test, in local conditions, the many new plants arriving as a result of the travels of the plant hunters, that made the Society put so much of its energy into developing a garden. The original proposal was for a site near Holyrood Palace but a much better solution was found when in 1823 the Society took on the lease of 10 acres of land in Inverleith, adjacent to the new site of the Botanic Garden, which was moving from the cramped quarters of its Leith Walk site. In 1825 William McNab, Curator of the Botanic Garden drew up a plan for the new garden which included something for everyone: orchards, a lockable experimental garden, a culinarium where ‘new and or little known varieties of culinary vegetables will be fairly tried’, an area for growing stocks for grafting and budding, nurseries, a wall for the finer kind of fruit trees, a rosary and compartments for perennials and annuals. The plan was very largely executed and the garden was known as the Experimental Garden. Donations of plants were received from all over the world, including 50 different types of strawberry sent by the London Horticultural Society; a cottage was built for the head gardener and James Barnett from the London Society’s garden at Chiswick appointed. Many shows were held in the garden, the first in August 1828, and there was a great 20th anniversary event in 1830. There was usually a military band with dancing, and for a time the shows became fashionable events, with beautifully dressed ladies arriving in carriages. In 1836 Barnett left under a cloud and the job was taken by James McNab, son of the Curator of the Botanic Garden, who presided over a period of prosperity and development of the garden. He was not only a very able garden manager but he was also skilled at raising funds, and an Exhibition Hall in which the Society could hold shows as well as meetings was completed in 1843. At the first meeting held in the new hall in May 1843, an exhibit of six Calceolarias from Arniston, a great William Adam house 21 miles south of Edinburgh, had been carried all the way by two men on a handbarrow. Each man was awarded 5s for his trouble. At this time the Experimental Garden had an extensive collection of fruit as well as of camellias and rhododendrons. McNab’s most ambitious project was the creation of a Winter Garden, a vast three gabled glasshouse with room for a promenade inside, which was opened in 1850. By this time though financial problems were looming.

Problems

The cost of running such an elaborate garden, plus the annual rent of £140, proved a heavy burden for the Society. In the late 1840s the membership went into a period of decline. In 1848 William McNab, who had done so much for the Society, died and his son James succeeded him as Principal Gardener at the Royal Botanic Garden. At a stroke the Society lost one of its main supporters and its key employee. The writing was on the wall for the Society’s Inverleith venture and after a lengthy period of negotiation the Experimental Garden was incorporated into the Royal Botanic Garden in 1864. It had lasted only 41 years. Sadly the great Winter Garden was demolished to make way for a new rock garden but a better fate met the Society’s Exhibition Hall. It became the Garden’s herbarium and remained in that use for 100 years until 1964; shortly after that it was then renamed The Caledonian Hall, thus provided a lasting memory of its early history as home to the Society’s events.

Amalgamation

In 1865 further relief to financial problems was offered by amalgamating with the Edinburgh Horticultural Society, which had many more members but a much shorter history. The name of the Society survived. Shows were the focus of affairs and, as earlier in the century, there were an astonishing array of classes and entries. Many of the competitors at these shows were gardeners to big houses or nurserymen, others were amateurs. This cross germination of horticultural knowledge between professional and amateur has always been one of the important functions of the Society.

Centenary and after

The centenary in 1909 merited a review of the Society’s history in the Gardeners’ Chronicle, but there do not seem to have been many special celebrations. During the First World War the shows ceased and all efforts were directed to growing food crops. Shortly after the War, the Society joined forces with the Scottish Horticultural Association; there was considerable overlap of both function and membership and both societies had suffered from the War. Although at the time the S.H.A. was the stronger society, the Royal Patronage was not transferable so once again the name of the Society survived. In 1925 all energies were devoted to the International Exhibition, a huge horticultural display, described by A.J. Macself in the Society’s Transactions as the ‘greatest and grandest triumph of all.’ The show was held in the Industrial Hall, in New Street, which later became the Central Bus Garage, and has now been pulled down. It was opened in a downpour by the Duchess of York, who was then the patron, but the visitors were not deterred, and over the three days of the show £1,700 was taken at the gate.

Royal Patronage

Royal Patronage has been an important factor in the esteem in which the Society has been held. In 1820 the Earl of Hopetoun, who was President at the time, obtained the Patronage of George IV, and in 1824 the Society received its first Royal Charter. Since then there have been two more Royal Charters, the latest in 2008. The Princess Royal is now the Patron having succeeded her grandmother, the Queen Mother, who was patron for 50 years.

Publications

The Society’s recent history, like its past, has been a matter of ups and downs. This is seen clearly in the Society’s publications. Unlike the London Society whose Transactions were initially produced to the highest standards with beautiful hand-coloured plates, (although these subsequently proved too heavy a financial burden) publications have never been elaborate. The main publication of record which started out as Memoirs, ceased publication for most of the 19th century, then from 1921–9 it became Transactions and in 1950 was revived as The Journal and has now settled down as The Caledonian Gardener. (Thanks to Anna Buxton for the historical overview.)